In the shadow of the towers of new Beirut, the ruins of ancient Beirut have literally been dismembered and piled up at the edge of town.

It may be hard to believe today, but ancient Berytus was a very prominent city in the Roman empire, one of a handful of Roman cities to contain a law school, which played a key role interpreting and producing the cannon of Roman law, foundational to legal systems across the world today.

Did these columns come from the law school or did they come from the famous chariot race track of Berytus that once hosted 1,400 gladiators in a single day? Or did the columns belong to the city’s Roman theatre, its baths, churches, gates or colonnaded roads?

The sad answer is we don’t know and we may never know. Piecing together the story of these columns and the spatial history of the city may now be impossible according to a source with the Directorate General of Antiquities (DGA) quoted in L’Orient Le Jour, which broke this story a couple of weeks ago.

“Since these stones have not been numbered, it is of course impossible to know to what specific sites or constructions they belonged.Unless the scientific data, formerly collected by the intervening specialists, have been archived … ”

So how could this happen? In the 1990s, Beirut was reportedly the biggest archaeological site in the world, with teams from universities across the globe working in its trenches.

I had a closer look at the ruins last week after blogger Elie Fares pointed the site out, following up on the L’Orient piece.

The columns were hard to find because they are literally invisible from the new waterfront road:

… tucked below the dirt patch, near the water’s edge:

Upon closer look, there were no labels in sight. In fact the ruins were haphazardly piled on top of one another, not even slightly spaced apart:

One was barely balanced on a flimsy piece of wood:

Yet all this seemed uncontroversial to the new culture minister, Ghattas Khoury, who noted that the columns were “well-organized” and “monitored” by the Ministry of culture and “everything is proper and well-preserved,” as he said in this video shared on Twitter.

Minister Khoury, a surgeon with no background in archaeology according to his bio, said the ruins will be carefully moved to Beirut’s park, Horsh Beirut, seemingly as decorative pieces.

وزير الثقافة #غطاس_خوري خلال جولته اليوم في الزيتونة بي لتفقد عملية نقل الاعمدة الاثرية الموجودة منذ العام ١٩٩٠ في محيط منطقة البيال pic.twitter.com/u0NS4YqPYo

— Ghattas Khoury (@Ghattask) May 4, 2017

The minister rejected criticisms of the government’s handling of the ruins, vaguely laying blame at those who participated in the anti-corruption protests of last year “which led to nowhere.” He also took aim at MP Sami Gemayel who delivered a Facebook live video earlier in the week, angrily questioning the column’s placement after reading about it on social media, and likening the ministry’s handling of ruins to that of extremist groups destroying heritage.

“These are priceless, do you know what that means,” Gemayel shouted. “You are just like ISIS.”

“You don’t protect the country from ISIS, we all protect the country,” responded Minister Khoury, who counter accused critics of “destroying the ministry of culture.”

The columns had been placed in storage around 1992-1993 by the controversial multi-billion dollar real estate firm Solidere, Minister Khoury claimed, adding: “Solidere moved them because they want to work on the marina. And they let us know…”

It seems Khoury was not referring to the yacht marina but rather the giant piece of legally dubious reclaimed seafront he was standing on, known as the “waterfront district,” Soldiere’s upcoming project, worth billions of dollars, as I had reported on previously. Thus the ruins apparently had to be moved to make way for more luxury real estate towers.

📹 الجزء الثاني: وزير الثقافة #غطاس_خوري خلال جولته لتفقد عملية نقل الاعمدة الاثرية الموجودة منذ العام ١٩٩٠ في محيط منطقة البيال pic.twitter.com/CzqRHWKfBw

— Ghattas Khoury (@Ghattask) May 4, 2017

But how is it that a private real estate company came to be responsible for housing and moving these ruins instead of the government?

In many ways, the story of these columns can be seen as a metaphor for how archaeology has often been handled during the postwar reconstruction period.

While reporting for the BBC on the discovery of ancient Beirut’s Roman chariot race track, I spoke to the former head of archaeology at the American University of Beirut who was blunt in her description on how ruins have been handled both in the capital and across the country:

“They keep everything secret. People focus on Beirut but they have no idea how many more substantial things are being destroyed across Lebanon,” said Professor Helen Sader.

Since publication of the piece, the chariot race track has now been completely gutted to make way for a bank and luxury villas owned by another minister.

Meanwhile Solidere and other archeologists who worked for company continue to present their reconstruction and archeological preservation efforts as world leading at conferences in Lebanon and around the world. But with ruins tossed in a pile with no labels, something has clearly gone wrong.

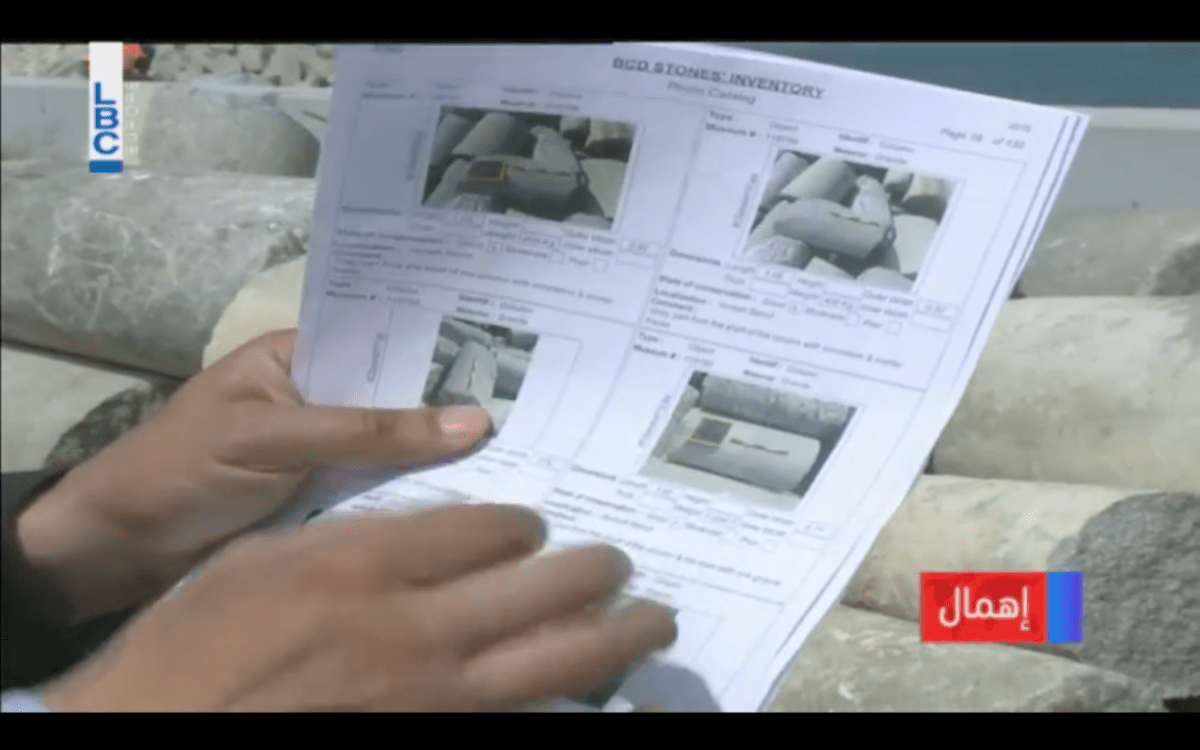

Perplexingly, the head of the antiquities department, Sarkis Khoury, claimed in a revealing LBC interview that as the columns are moved, each would be labeled according to its size and physical dimensions.

But why are the columns being labeled now instead of when they were first excavated? After all, it is not the length and height of the columns that tells their story, it is primarily the location where they were found, the archeological context, what structures or artifacts they were attached to and or found around them, that helps us date them and understand their usage. But now most of those excavations have been destroyed.

Director Khoury noted that the ruins would be distributed in gardens and public institutions across Lebanon “so the Lebanese people can benefit from them.” Many have already been moved to the city’s only park, Horsh Beirut.

But does the public really benefit from columns with no identity? Columns that tell no story? Random slabs of granite laying on the ground with no meaning? How did such a massive archeological effort end this way? Why are the columns not being showcased across Beirut where they were found to give people a sense of the Roman city?

Some government archaeologists complain that the public does not appreciate history, but how can they do so if there are no signs or indications of what these stones and structures mean?

I plan to get more answers to these questions in an investigative piece I am working on with the support of a crowd-funding campaign by Press Start. Your comments or suggestions are always welcome.

In the meantime, one major thing has changed since the 1990s and that is social media. Posts by activist groups as well as prominent Lebanese bloggers such as Gino Raidy, Elie Fares and others have helped shed light on these issues, which were poorly covered by mainstream media in years past. But even the mainstream media is changing and becoming more aggressive in demanding accountability, as the reports quoted in this post by LBC’s Sobhiya Najjar and L’Orient’s May Makarem, show.

Going forward, let’s hope that with more media coverage and public debate, ruins won’t be brushed aside so easily in the future and we’ll be able to learn more about ancient Berytus as excavations and discoveries are likely to continue.

1 comment